|

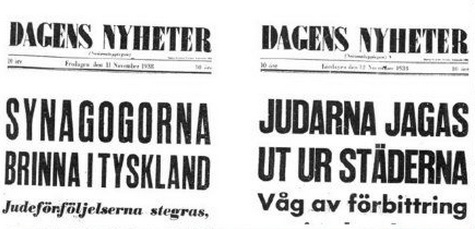

Jurister tjänade troget Hitler, så att statsförvaltningen och nazisternas ”rättsväsende” fungerade. Just nu finns på Svt Play en serie om två delar: Gisslan

hos SS ,

som är mycket sevärd. Efter mordförsöket

på Adolf Hitler, den 20 juli 1944, arresterades mängder av människor och deras

familjer. Familjer med barn sattes i läger och skulle användas som gisslan. Här

berättas några av de gripnas historia. I den senare delen finns ett antal

scener när deltagare i attentatet mot Hitler dömdes av skränande domare, Nazisternas

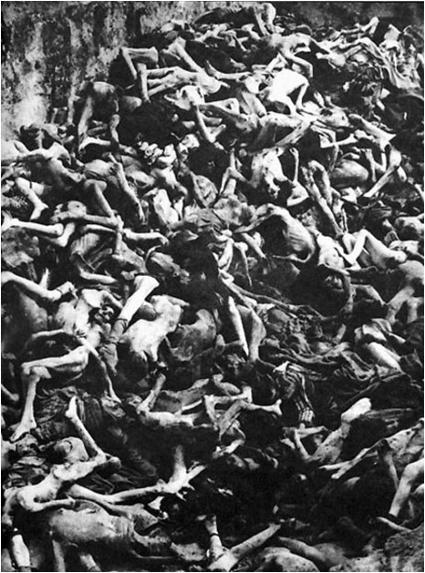

jurister och domare har alldeles för litet uppmärksammats. Förintelsen sköttes av förvaltningen och tangerade bara domstolarna. Mertalet judar, romer och homosexuella mfl fördes till koncentrationsläger eller bara

dödades utan rättegång och dom i Nazityskland. I denna polisadministration och

Justitieministeriet och Folkdomstolen Juristen Otto Thierack var mellan 1936 och 1942

ordförande för Folkdomstolen och från 1942 till 1945 riksjustitieminister.

Thierack deltog aktivt i att utforma Tredje rikets rättssystem till ett

terrorinstrument och utfärdade återkommande anvisningar för domar och tolkning

av lagstiftningen. I oktober 1942 skrev Thierack i ett brev till Martin

Bormann: ”I avsikt att befria det tyska

folket från polacker, ryssar, judar och zigenare, och i avsikt att göra de

östra territorier som har inkorporerats med Das Reich tillgängliga för tyska

medborgares bosättning, ämnar jag överlämna den straffrättsliga myndigheten

över polacker, ryssar, judar och zigenare till Reichsführer-SS (Himmler). Detta

gör jag i den principiella övertygelsen att rättsväsendet endast i ringa mån

kan bidra till utrotningen av dessa folkslag.” Thierack begick självmord i

amerikansk fångenskap. Folkdomstolens

mest framträdande jurist var Roland Freisler och var den som ledde domstolens

arbete från och med augusti 1942 till och med februari 1945. Under andra

världskriget var Freisler beryktad för den folkdomstol han ledde, för sin

summariska syn på rättegångarnas funktion och de kränkningar i ord och handling

han utsatte de åtalade för. Han kunde exempelvis neka en åtalad att bära livrem

för att under rättegången håna denne när byxorna hasade ner. Han avkunnade

domarna mot motståndsmännen från 20 juli-attentatet 1944 och ytterligare fler

än 3 000 dödsdomar under tiden han var president i Volksgerichtshof 1942–1945.

Domarna rörde huvudsakligen politiska

motståndare som ville avsätta Adolf Hitler och avsluta kriget. De vanligaste

avrättningsmetoderna var hängning eller giljotin. Juristutbildningen anpassades

till det nazistiska tänkesättet. Uppgifterna är från Law, Justice, and the Holocaust.

Lagen blev ett medel att förverkliga Förintelsen. “Indeed, law was part of the Holocaust,” said Martha Minow, dean of Harvard University’s Law School, . Minow referenced the courts in Nazi-occupied France. To please the Nazis, Vichy legal authorities implemented racial laws with unprecedented speed. As Minow put it, “judges raced to create even more onerous laws” than were practiced in Germany. The so-called 'People's Court' of Nazi Germany, set up outside of normal constitutional frameworks, 1944 (Public domain)

Tyska domare och domstolar dömde i Hitlers anda och var viktiga för att genomföra Hitlers politik German judges and courts as the key rubber-stamps for Hitler’s policies. Minow spoke about serving on the Kosovo post-conflict peace commission 18 years ago. Time and again, said Minow, people in the region told her that “independent courts” were needed if the former Yugoslavia was to heal. In addition to restoring public confidence, courts can punish the perpetrators of atrocities, set up “truth commissions,” and ensure victims receive reparations. Apart from due process, Minow said that all societies need “upstanders” – people who resist injustice by attempting to correct it. “The responsibility for justice is in the hands of the people, said Minow. “The willingness of bystanders let’s bad things happen. That permits something like the Holocaust to happen.” Minow recommended focusing on “the banality of virtue” — a spin on philosopher Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil” assertion, wherein Nazi perpetrators were motivated not by ideology, but by ordinary social needs. The exhibit frames German judges and courts as the key rubber-stamps for Hitler’s policies. Years before Germany’s descent to genocide, Third Reich citizens with dissenting opinions were sent to concentration camps. The legal framework for those camps, along with Nazi racial laws, was upheld by thousands of law professionals. “Judges were among those inside Germany who might have changed the course of history by challenging the legitimacy of the Nazi regime and hundreds of laws that restricted political freedoms and civil right.

Tyskland har svårt att frigöra sig från nazisternas legala arv. Germany still

untangling Nazis’ legal legacy. Germany’s justice ministry is embarked on a

wide-ranging effort to examine the influence that the Nazis had on the

country’s legal system, including the role some German officials played in

preventing former Nazis from being prosecuted after the war.

The project, 70 years after

the end of World War II, comes amid a fresh push to bring surviving Nazi war criminals

to justice. Two trials of alleged death

camp guards would have been impossible until recently due to legal hurdles and

the existence of a network of former Nazis who worked as lawyers, prosecutors

and judges after the war. “Too many who bore guilt covered for each other,”

Justice Minister Heiko Maas told The Associated Press in an interview. “Even at

the start of the 1960s, 80 percent of the judges at the Federal Court of

Justice had been judges under the Nazis. That illustrates the extent to which

the German justice system failed.” Efraim Zuroff, Simon Wiesenthal Center, cautiously

welcomed the move: “The stakes are certainly not as high as they once were.

Having said that, this is a very, very important historical inquiry that I

think will have an important impact on the way German society views the

judicial effort and the whole question of bringing Nazis to justice. There’s no

question that the initial decades could be classified as a very serious

failure.”

“It’s never too late for justice” Among the

obstacles to prosecuting former Nazis was that German law required proof of

direct involvement in a killing for a murder charge — the only crime not

covered by the statute of limitations. This meant that thousands of people who

played an important role in the Holocaust weren’t prosecuted. That changed in

2011 when a German court accepted Munich prosecutors’ new legal reasoning in

the case of John Demjanjuk. They argued that Demjanjuk was a guard at Sobibor,

a death camp whose sole purpose was murder, so even if there was no evidence he

participated in a specific crime he could be convicted as an accessory for

helping the camp function. The conviction unleashed an 11th-hour wave of new

investigations, even though it wasn’t legally binding because Demjanjuk, who

always denied serving as a death camp guard, died before his appeal could be

heard. “German jurisprudence took a long time to conclude that it wasn’t

necessary to play a personal, concrete, active part but (that it was

sufficient) if someone had worked elsewhere to make the death camp function in

the first place,” said Maas. “I think that’s absolutely right.” Though most suspects are now in their 90s,

holding them to account is important for survivors, victims’ families and the

German state,” Maas also said it was important to convey to a new generation of

law students how post-war Germany initially failed in that task. “The point of

this project is to acknowledge the greatest mistake of Germany’s post-war legal

system, which was that the justice system — which between 1933 and 1945 was nothing

but a stooge of the Nazis — didn’t help to atone for the Nazi crimes after

World War II in the young Federal Republic,”. I boken Daniel

Stahl, "Nazi-Jagd: Südamerikas Diktaturen und die Ahndung von

NS-Verbrechen" https://www.expressen.se/andra-varldskriget/svenske-ss-mannen-kreuger-hjalpte-nazisterna-att-fly-efter-kriget/

pekas det tyska rättsväsendet ut som skyldigt att ha hjälpt en stor grupp nazister i flykten till Sydamerika. Även det franska rättaväsendet anses ha

medverkat till att Frankrikes skuld i

Förintelsen inte klarlagts för att på så sätt inte kasta ljus över egen skuld.

Juridikstudier

är alltså ingen garanti för respekt för Mänskliga rättigheter och demokrati Domare och överhuvudtaget jurister omger sig ofta

med en air av objektivitet och försöker ofta med kaftaner, ”kardinal”-hattar

eller peruker utplåna eller dölja att de är vanliga människor - visserligen med

särskilda juridiska kunskaper – men människor med fördomar, känslor och

eventuell privat agenda. Även det formella språk kan medverka i maskeraden.

Jag tror inte att jurister annat än undantagvis är illvilliga eller korrupta,

men jag vet att det finns sadister, lögnare, icke-demokrater osv bland mina

kollegor. Exempelvis undrar jag om det är fler jurister än jag i Sverige som

mår illa av den rättstillämpningen med ovetenskaplig åldersbestämning och

utvisning trots ömmande skäl. Man förstår ju också att det finns jurister som tummar

på

2018-04-02, 19:33 Permalink

Andra bloggar om: Jurister Sd Fascistiska rötter Nazism Hitler Uppgbörelse med krigsbrott Mänskliga rättigheter Demokrati Bo widegren Nya kommentarer kan ej göras för detta blogginlägg! |

NÄTVERKSPORTALEN WWW.S-INFO.SE

NÄTVERKSPORTALEN WWW.S-INFO.SE  BLOGGPORTALEN WWW.S-BLOGGAR.SE

BLOGGPORTALEN WWW.S-BLOGGAR.SE  FORUMPORTALEN WWW.S-FORUM.SE

FORUMPORTALEN WWW.S-FORUM.SE